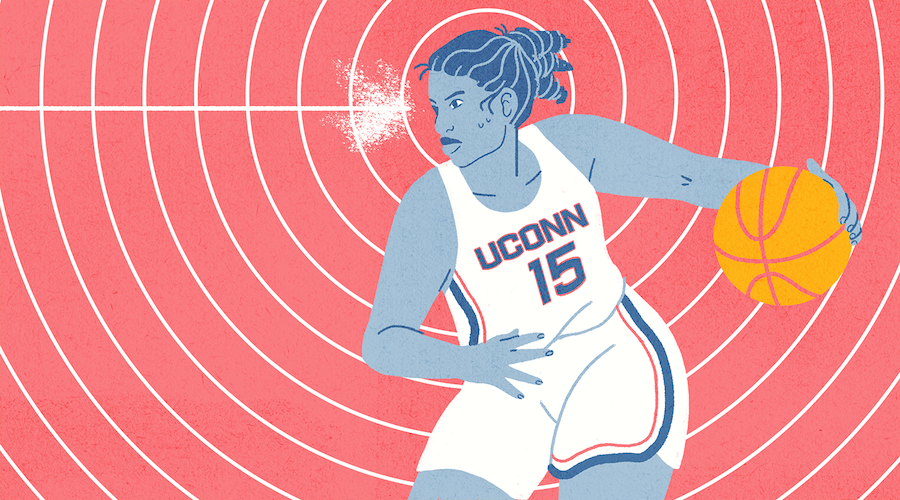

Gabby Williams is (Almost) Everywhere

The play was close to irrelevant, statistically speaking, like most plays involving the University of Connecticut women’s basketball team are. It added a decimal-sized flake to the accumulation of win-probability snowfall. The Huskies already led fourth-ranked Louisville 13-3 in their mid-February matchup when Crystal Dangerfield’s first-quarter jumper fell off the rim, but senior forward Gabby Williams reacted to the miss with absolute gusto, as if what was hanging in the balance was not UConn’s nearly assured 136th victory in its last 137 games but, well, everything. She crashed in from the right wing, out beyond the three-point line, to the left block. She pulled down the rebound in both hands. She looked over her left shoulder in the direction of the lane, spun on her right foot, and snapped a pass past two defenders’ ears to the microscopically open Napheesa Collier, who laid it in. That was the way the margin grew from 10 to 12; it would soon get to 22.

It was a remarkable sequence soon to be forgotten amid the run to follow, the piling-up of steals and layups and three-pointers. That’s the way with UConn – again undefeated and heavily favored to win a national title in a couple weeks. As with so many iterations of the team in years past, these Huskies dominate seemingly at whim; the college ranks have not yet produced the defense that Dangerfield cannot blur through, that Katie Lou Samuelson cannot shoot over, that Collier cannot pin to her back. But if the range of talent, and the totality of the teamwork it operates within, makes for beautiful and winning basketball, it is also produces an odd feeling of self-summary, of a real-time recap. Particulars are forever being gathered into the larger thesis.

What I’m saying is: It can take a little work, in this context, to consider any one player as an individual contributor, something other than a fleeting embodiment of a general, sleekly proficient Huskie-ness. What I’m also saying is: In the case of Gabby Williams, that work is well worth it.

The basic info on Williams is not all that different from that of her teammates and predecessors. She stands five feet eleven inches tall and rates exceptionally in every athletic category. As a high-schooler in Nevada, she was one of the nation’s top players; she also excelled in track and field and qualified as a high-jump alternate for the 2012 Olympics. She came off the bench her freshman year at UConn (winning the American Athletic Conference’s Sixth Player of the Year award), made a few starts as a sophomore, and as a junior was named a second-team All-American and the national Defensive Player of the Year. This season, she numbers among the fifteen finalists for the Wooden award.

Most anyone who plays enough minutes for Geno Auriemma becomes similarly credentialed; two other Huskies are also Wooden candidates. But where her teammates seem to chart basketball’s possibilities, surveying their options and hitting their jumpers, Williams interrogates it. In the third quarters of 30-point blowouts, she wears an incongruously anxious expression, as if worried even then about opportunities missed, chances blown. As a group, UConn wants to make the right plays. Williams wants to make all of them.

Her stats offer a window into her activity; she leads the Huskies in assists and steals and ranks near the top in rebounds and field-goal percentage. To watch her play for even a quarter, though, is to forget the numbers. Williams sees the court like a satellite and moves like a torpedo. On defense, she monitors three passing lanes at once. On offense, she dispenses the ball from her perch at the free-throw line, forgoing the obvious – that pin-down springing Samuelson – in favor of some one-handed, seam-splitting premonition. And when you see her running in the open court with a thundering, high-kneed gait that it would hurt badly to get in front of, the strategic question of how to limit her turns moot. You just wonder who would be reckless enough to try.

“She plays the way Lawrence Taylor played linebacker,” Auriemma says of his star forward. “Single-handedly, she can ruin a team.” Those are words – “Lawrence Taylor,” sure, but also “single-handedly” and “ruin” – not normally associated with the slickest cooperative in college basketball. But in the case of Williams, they are the only ones that fit. Like Taylor, she seems personally affronted that she can’t be everywhere, doing everything, at every moment. She takes the floor as if to whittle away the impossibility from that objective.

In their NCAA tournament opener Saturday afternoon, UConn did the kind of casual record-obliterating they’re good for once or twice a year, dropping 94 points in the first half against St. Francis en route to an 88-point win. Playing with a sore hip that had kept her out of an AAC tournament game the week prior, Williams was her endline-to-endline self, putting up 16, nine, and six in just 22 minutes. No one moment stood out, the margin too big and the competition too sacrificial. Still, as ever, there was an urgency about her that nobody else matched, visible in the unneeded imagination behind her passes and in the suddenness of her movement. The particulars of opponent and scoreboard didn’t matter. She was playing in a game, so she wanted to take whatever she could.